Bill to allow towns to cut school spending advances

WHAT WOULD THE IMPACT TO NEW FAIRFIELD BE IF WE JUST REDUCED TEACHING POSITIONS IN THE LOWEST GRADES ... BECAUSE OF ENROLLMENT DECLINE?

By Jacqueline Rabe on March 25, 2011

A bill to allow cities and towns to cut school budgets when enrollment declines--opposed by educators but backed by municipal leaders and Gov. Dannel P. Malloy--won key approval from the legislature's Education Committee Friday.

Local governments are currently barred by state

law from cutting the amount they spend on education, even in towns where enrollment has dropped, such as Meriden, New Britain and Bridgeport, where numbers have fallen between 6 and 9 percent.

"We'll certainly address this," Sen.

Andrea L. Stillman, co-chairwoman of the Education Committee, said before committee members unanimously voted in favor of a

bill that would

allow towns to cut $3,000 for every one-student drop in enrollment.

Sen. Andrea Stillman

But education officials say allowing towns to cut based on enrollment declines would be disastrous, since many of the costs are fixed for schools.

"If you lose only one student you will have no savings. We have to hit that critical mass before savings are achieved," said Patrice McCarthy, general counsel for the Connecticut Association of Boards of Education. "You still have to pay for teachers... for just about everything."

She said a formula must first be developed to accurately determine what a district saves as enrollment declines, and then school boards may be able to back a reduction in spending.

State funding does take student enrollment figures into account when allocating education aid to cities and towns, but towns are held to a different standard.

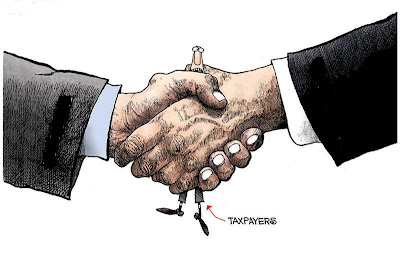

"That doesn't work," said Rep. Timothy J. Ackert, R-Coventry, of the prohibition on towns' cutting spending. He also urged the committee to go one step further and allow towns to cut the "actual amount" towns realize in reduced costs, which he expects is more than $3,000 per student. Current spending for public education statewide is about $10.4 billion this year and almost 70 percent of all municipal spending goes to pay for education, according to the Connecticut Conference of Municipalities. "We are requiring towns to pay for students that aren't in their schools. That is taxpayers paying for that," said Stillman during an interview. She said last year a handful of towns brought up this problem, and lawmakers responded by carving out a one-time exception that allowed towns to reduce the amount they spend on education.

But lawmakers are considering making it the rule and not the exception, so towns don't have to plead their case in Hartford when they want to make cuts.

Malloy -- who proposed the change the committee unanimously approved - said last month he

supports allowing towns to reduce their spending, but only when towns experience

"a sizable reduction" in enrollment.

This proposal has no qualifying threshold in the amount of students that a district must shed before cutting $3,000 per student.

And even then, McCarthy said $3,000 is way too much to allow towns to cut.

Jim Finley, executive director of CCM, acknowledges if state lawmakers untie town officials hands and allow them to reduce education spending, tensions between school and town officials will undoubtedly arise.

But he says it's a battle that worth having.

"It's not cutting their budget. It's allowing towns to pay what it is realistically costing to educate a child," he said. "Why should the education side of their budget be immune from cuts?"

Bart Russell, executive director Connecticut Council of Small Towns, said he thinks towns will get through the tension.

"It will create some tensions... But there is an understanding that we are in it together. I think that conflict is going to be minimal," he said.

Finley and Russell also said only allowing towns to cut when enrollment declines doesn't go far enough -- they want towns to be able to cut whenever they find savings.

"We are blind to the opportunity to get some savings," Finley said.

But McCarthy said the impact of that would be harsh on schools.

"What you'll have is a smaller pool of resources for students," she said.